Diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs) place a huge burden on healthcare systems. Occurring in around 10% of patients with type 1 and 2 diabetes, these slow-healing wounds are problematic for patients and far from straightforward to treat. Around 450,000 people in the UK will develop such an ulcer at some point in their lives, a minority of whom will eventually require amputations. Soberingly, half of DFU patients will die within five years of diagnosis – a higher mortality rate than many cancers.

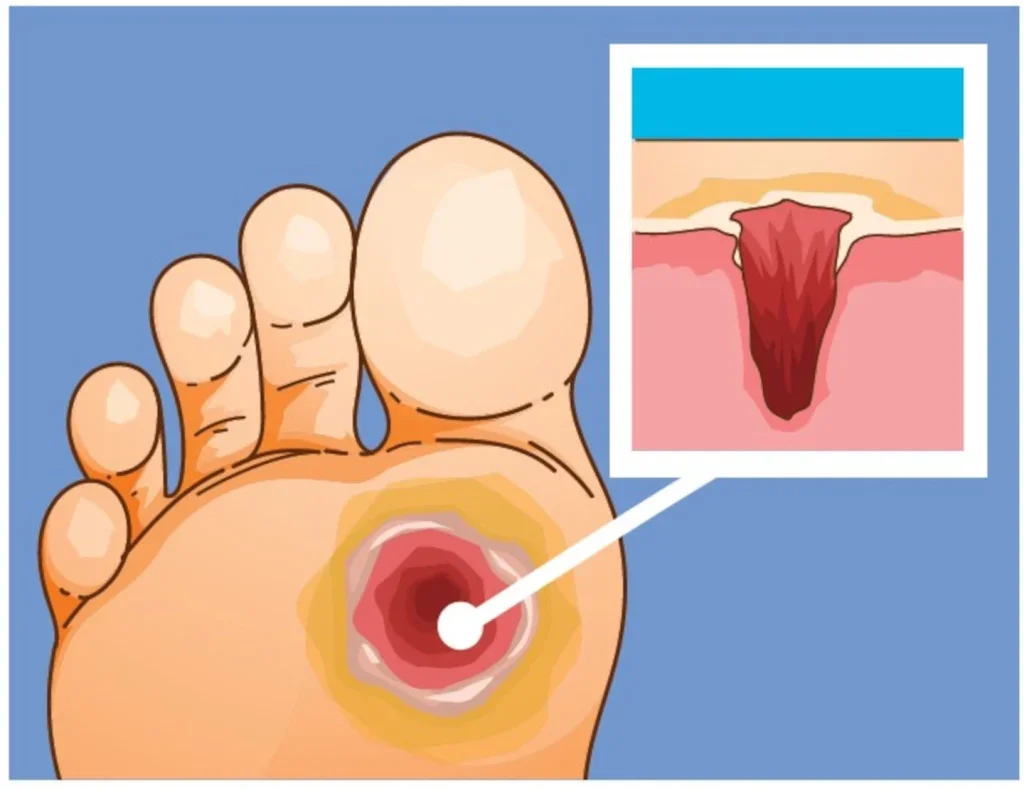

When blood sugar levels remain persistently high, or fluctuate dramatically over a long-term period, the patient can develop neuropathy. This in turn can lead to a loss of sensation in the feet and a lowered capacity for healing – and can spell trouble. Since patients lose their protective response mechanisms to pain, they are unable to detect minor trauma such as blisters or abrasions, which can develop into DFUs if inadequately treated. Although the ulcers don’t always hurt, they do need to be treated to lower the risk of infection and other complications.

“The NHS spends around £1bn a year on the management of diabetic foot ulcers, which is equivalent to around 1% of total NHS spend,” remarks Dr Paul Chadwick, visiting professor in tissue viability at Birmingham City University. “A lot of that is spent on treating non-healing DFUs, where the focus is on just maintaining them rather than trying to heal them.”

According to NICE guidelines, patients ought to be referred to a multidisciplinary team within 24 hours of presenting with a DFU. The sooner the better: more than half are ulcer-free at 12 weeks if they are seen within the first two days, whereas little over a third attain this outcome if they wait more than two months. Once safely in the hands of specialists, they can receive the appropriate care – offloading (a modified orthotic), cleaning, debridement (removal of dead tissue) and a dressing.

“A lot of DFUs have a local hypoxia, and if it doesn’t have oxygen, it doesn’t go through the natural process of healing.”

Dr Paul Chadwick

“The standard of care is good if you can give the standard of care,” says Chadwick. “But accessing the wound care dressings can be quite difficult, and access to offloading devices can be really difficult. So access to services is a big barrier, and the services that exist are under-resourced.”

In the US, the problem is starker still. Here, DFUs affect 1.6 million people every year, with advanced-stage ulcers costing upwards of $50,000 per wound. There are significant disparities in access to treatment. “Because the development of a DFU is such a complex process, and there are many underlying pathophysiological things going on in our patients, it’s important that we do a full wound assessment at every single visit,” says Dr Windy Cole, an adjunct professor at Kent State University College of Podiatric Medicine. “We lack good multimodal therapies, which act in different ways to help optimise the wound environment in these very complex and at-risk patients.”

A new hope

Clearly, there is a need for better treatment options, especially in patients whose wounds aren’t responding to conventional care. One promising candidate is topical oxygen therapy, which has been associated with successful outcomes in suitable patients. Although there are around a dozen different products on the market – among them haemoglobin spray, oxygen wound spray and continuous delivery of oxygen – all work by administering some muchneeded oxygen to the wound bed.

“A lot of DFUs have a local hypoxia, and if it doesn’t have oxygen, it doesn’t go through the natural process of healing,” explains Chadwick. “Quite often wounds get stalled at what we call the inflammatory stage, meaning they become chronic and much more difficult to treat.”

One trial, which looked at 72 patients with venous leg ulcers, found that their average wound size reduced by more than half at 13 weeks when treated with haemoglobin spray. Other studies have shown that twice as many chronic wounds healed by 8–16 weeks with the haemoglobin spray, compared to the standard of care.

The evidence base, as it applies to DFUs, has grown more robust in recent years with more high-quality trials in the literature. In 2023, the International Working Group of the Diabetic Foot recommended that topical oxygen therapy should be considered when caring for hard-to-heal DFUs. That’s a shift from 2019, when there wasn’t considered enough evidence to make a recommendation.

“There’s a been a shift over the last five years to say that, potentially, it’s something that we should be considering in chronic wounds,” says Chadwick. “I would always argue that you need to do the standard of care first, but if the wound size hasn’t reduced by 50% in four weeks, you should be using adjunctive therapies. Topical oxygen therapy is probably one of the primary ones there.”

Help where it’s needed most

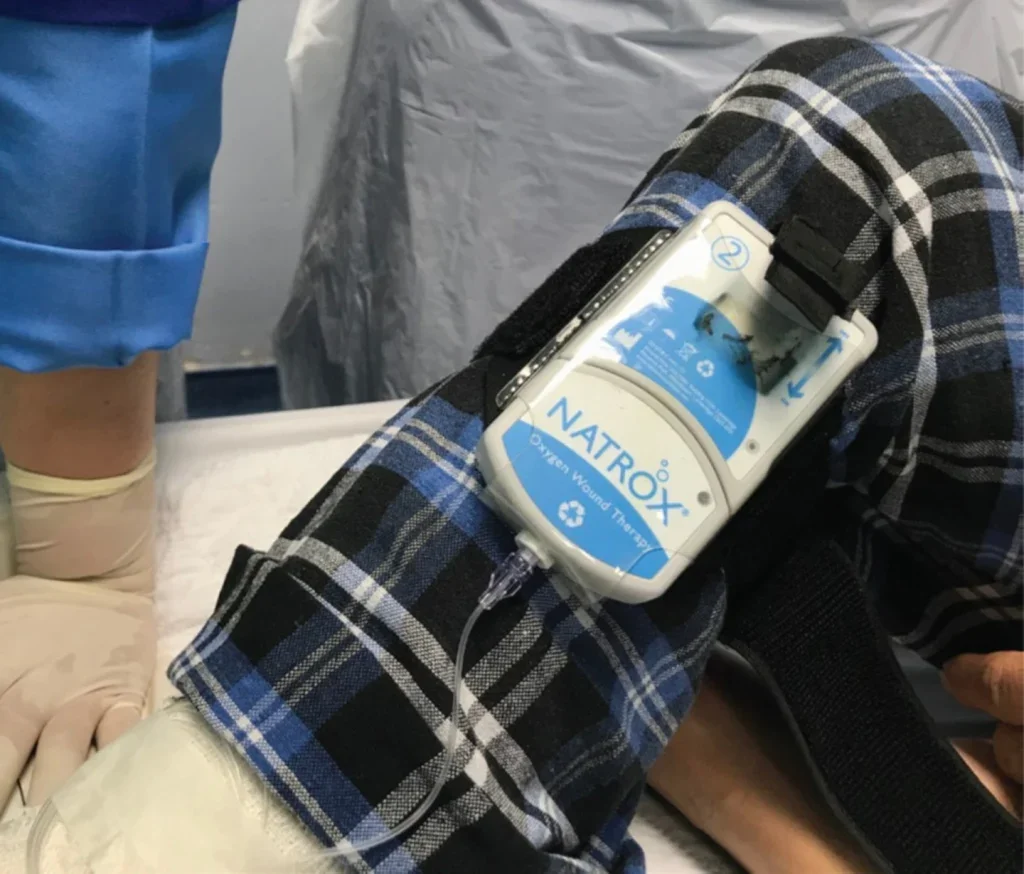

Cole is especially fond of continuous topical oxygen therapy, in which oxygen is delivered 24/7 to the wound via a wearable oxygen generator. The device is small – around the size of a mobile phone – and can be strapped to the limb, allowing the patient to remain mobile. “The device takes the room air and concentrates just the oxygen through an electrochemical reaction,” she explains. “The patient can continue to work or do their daily activities while the oxygen is being delivered to the wound.”

Her first introduction to this therapy came through her participation in a DFU trial, in which her patients anecdotally did very well.

This was borne out by the trial results: those who were treated with continuous topical oxygen therapy were more likely to experience complete wound closure, compared to those who had only received the (very rigorous) standard of care.

Cole has since published a series of case reports into its efficacy, having used it on patients with particularly complicated wound types. Through using near-infrared spectroscopy, she was able to assess the oxygen saturation in these wounds before and after applying topical oxygen therapy. “Week after week, we saw an increase in oxygen saturation in the tissues, and week over week, we saw a decrease in the wound area,” she recalls. “So as oxygen saturation went up, the area of the wound went down.”

She is now hoping to conduct further research, teasing out its exact mechanism of action. The study would look at gene expression in chronic wounds before and during treatment – how does a change in gene expression correlate with a change in the tissue?

“Patients often show a decrease in pain symptoms with application of continuous topical oxygen therapy, and it really happens almost immediately,” she says. “So what does that mean? And what are we doing for the wound that aids in that decrease in pain? Determining what genes are turned on or off in patients who receive topical oxygen therapy is a question I’d like to answer.”

While further research would be desirable – for some people, the evidence probably still isn’t enough, notes Chadwick – there is arguably a strong case for integrating topical oxygen therapy into health systems. As is always the case with a new medical technology, the biggest question mark surrounds the health economics: what is the true value of deploying this therapy considering its upfront costs?

Getting oxygen into the system

As matters stand, the technology is available worldwide, but health systems vary in what they deem worthy of coverage. Cole cites Mexico, India and Japan as countries where the technology has expansion potential. “In the US, it is available in the Veterans Affairs (VA) hospital system,” she says. “It is covered by Medicaid in certain states, while Medicare is going through the process of evaluating the evidence, to see whether it will cover the device and at what rate.”

In the UK, the treatment is being used in specialist centres. Chadwick says he is fond of the haemoglobin spray, because it doesn’t take much setting up. But it has yet to achieve broad application, largely due to concerns about the cost. “When you look at the cost of it over an initial period, it looks expensive,” he remarks. “But then, if you’ve done the health economics of it, you know that that it will help heal a wound heal more quickly and reduce rates of infection and hospitalisation.”

While it takes a long time to change clinical practice, the shift is beginning. NICE has published recommendations on the haemoglobin spray (Granulox) and the continuous topical oxygen therapy (NATROX) and was generally supportive about both. In terms of costs, Granulox works out at £125 for 30 applications, or 10 weeks of treatment, while NATROX is priced between £300 and £500 for 12 weeks of treatment. This should be set against the cost of managing an unhealed wound (anything up to £7,886 per person per year) and the cost of a diabetic foot amputation (up to £12,767).

“The cost of managing unhealed wounds is expected to rise about 40% over the next five years,” notes Chadwick. “But if we succeed in healing 1% more wounds, we will start to keep the costs more neutral, and if we heal about 4% more wounds, we’ll start to save money. So we need to start thinking differently about resource allocations.”

In Cole’s view, deploying continuous topical oxygen therapy is a ‘no-brainer’. “In my personal experience, I’ve had great success,” she says. “Patients find it very easy to use, they’re very happy with the pain reduction, and I think it helps support quality of life. Patients are not impeded by this therapy and heal faster, so I think the sky’s the limit.”