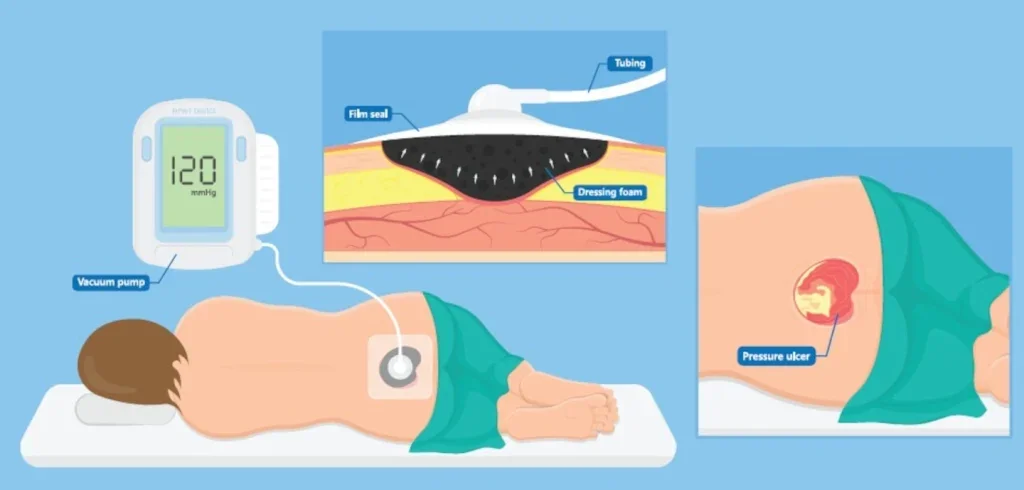

In 1995, Luc Téot saw a presentation at the annual meeting of the Wound Healing Society in Vancouver about a new method for treating wounds using negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT). The speakers, Dr Louis Argenta and Dr Michael Morykwas from Wake Forest University School of Medicine, only had a small window to explain the kit they had developed – a special foam with tiny pores that would go into the wound, a silicone film that would seal the wound and a vacuum pump to draw out fluids, promote healing and lower the risk of infection.

At the time, this wound care treatment was revolutionary, but over the past three decades, NPWT has become a mainstay in healthcare practitioners’ wound care toolkit and today, it is accepted practice to treat various kinds of wounds ranging from acutely infected wounds to complex combat wounds and skin grafting. That said, it hasn’t all been smooth sailing. Téot, who is now assistant professor of plastic surgery and honorary head of the plastic surgery department at Montpellier University Hospital in France, has followed NPWT from day one back in Vancouver through patent battles when the discipline started to hit the headlines, right up to 2024, when techniques have advanced far beyond Argenta and Morykwas’s initial wound care kit.

However, as companies and researchers have continued to advance the technology, commercialising various, more complex, versions of NPWT, adoption has not kept up due to a combination of factors including insufficient training on the latest methods and resistance to change. For this reason, Téot decided to join forces with several of his colleagues and the European Wound Management Association (EWMA) to create new guidance designed to change that.

Not only does EWMA’s recently-released report – an update to a document that was initially published in 2017 – outline the major advancements in the field in recent years, but it also addresses the challenges and opportunities related to the clinical application of these systems both in hospitals and at home, with practical suggestions on how to overcome them.

Post-operative negative pressure

One of the most important developments in the field was the advent of closed incision negative pressure therapy (ciNPT), a method that was first introduced in 2006 and significantly advanced by Christian Willy, a German surgeon and one of the co-authors of the EWMA guidance, to prevent infections after major surgeries, such as heart surgery or removing and changing a prosthesis. In this modification of NPWT, negative pressure therapy is applied immediately postoperatively over closed incisions, primarily with the aim of preventing the incidence of surgical site infections (SSIs), as well as other surgical wound complications, like seroma and hematoma.

And it’s been found to work; most of the 69 studies comparing ciNPT with standard post operative wound management in randomised controlled trials show that its use is associated with a decrease in wound complications, wound dehiscence, hematoma/seroma formation and reduction in SSIs. Most recently this year, Smith+Nephew’s PICO negative pressure wound dressings for closed surgical incisions was found by NICE to provide better clinical outcomes than standard dressings in patients at high risk of SSIs at a similar overall cost. The second important modification of NPWT is NPWTi-d, whereby a liquid – usually saline, but sometimes antiseptic or antibiotic substances – is introduced into a sealed wound to modify the healing process by boosting the formulation of granulation tissue. This system can take the pressure off nursing staff as a computer automatically controls the instillation therapy – the amount of fluid and time for which the substance is allowed to take effect, for example, 20 minutes. It also controls the duration of the suction period (for example, four to six hours) and then, after a set time during which the instillation is left to take effect with no suction applied, it removes the solution by suction so standard NPWT can be continued.

“It’s a fantastic treatment,” Téot says, “However, uptake has been slow in the last decade; the addition of instillation to NPWT adds a level of complexity in the care process, which can in practice lead to difficulties.”

Téot and his colleagues have also adapted this method for use as a debridement tool, by introducing a foam with regularly spaced 1cm holes covered by a second, non-perforated foam layer. This dual-layer foam scrapes away and removes dead tissue, with the first layer detaching tissue and channelling it upward and the second layer removing accumulated debris. This system accelerates wound cleaning, transforming NPWTi-d from a fluid-draining tool to one that handles debridement and promotes healing, preparing the wound for skin grafts, artificial dermis, or natural healing.

“It’s a useful system because debridement is a job that neither nurses nor surgeons like to do. Surgeons typically prefer amputations over debridement, as they lack training in removing necrotic tissues, while nurses are not used to going deep into wounds,” Téot explains. “However, NPWTi-d is more complex than standard NPWT, so it does require highly specialised nurses to operate it. Therefore, adoption is limited to specialised wards with trained personnel. While the market for this technology is small, it exists and functions effectively in the right settings.”

The shift to primary care

EWMA’s new guidance also explores NPWT’s increasing use in the primary care setting and the benefits this approach brings. For example, in a study from the Czech Republic treating diabetic foot ulcers, the cost for treatment with NPWT outside the hospital compared with inpatient treatment was significantly lower – €600 versus €1,300.

Meanwhile a report from the NHS in the UK also showed lower costs when using NPWT in outpatient settings, along with other benefits including the possibility of earlier discharge from hospital. In addition, a study comparing children treated with NPWT involving 1,621 inpatients and 1,563 outpatients showed that treatment in an outpatient setting was associated with both lower costs and lower complication rates.

At present, however, primary care is generally limited to the standard version of NPWT, with the notable exception of a pilot program for NPWTi-d in France called ‘Hospitalisation at Home’. The service provides a medical visit twice a week, a paramedical service every day, plus emergency call availability 24/7 offering technical and logistical support. According to EWMA’s guidance, this structure has made it possible to reduce the hospital stay time and, in some cases, even to avoid further hospitalisation. But Téot admits there remain challenges with its implementation.

“If a nurse is carrying out NPWTi-d on a wound in a difficult location, such as under the buttocks, the liquid may push the film and cause some leakage, which causes difficulties for nurses and patients. To avoid this, we train the nurses not to put too much liquid into the wound and to do it frequently – this training is absolutely essential to the success of the project.”

Bringing NPWT to remote areas

Indeed, the key roadblock to the adoption of the more advanced NPWT techniques outlined in the EWMA document, whether they are being used for incisions or complex wounds, says Téot, is education. “It’s the key to all improvements. No matter what country you’re in, wound healing is not a discipline in itself. It’s covered by many specialists in diabetes, in geriatrics, in dermatology, in vascular [treatment] and much more, but this is not enough. We need better training in nursing schools and faculties of medicine.”

In some cities, there are high-quality training programmes run by the companies that have commercialised the systems. “Every three months in Amsterdam and London, there are training programmes on cadavers for the nurses that work in this area and are interested. They learn how to use the foam, how to cut it in the right way, to cover the wound and regulate the machine. Companies have a responsibility as teachers,” Téot notes.

In addition, in France, there is an inter-university diploma with Montpellier and Nantes. “Students are not only trained on theoretical wound care, but they can also come to the anatomical lab and have two days of going inside wounds and applying negative pressure,” Téot explains. However, in remote areas, the educational possibilities simply aren’t there, meaning there is a lack of wound care experts to deal with these sorts of injuries. It’s a cause Téot has taken up. “I really feel that telemedicine is where my focus needs to be now because it’s the best hope of improving things for patients in these areas,” he says. “It’s the only way they can have access to an expert within 24 hours.”

The project he is leading for the French health ministry is a trial in the Occitanie region in the south of France. “We have 14 people here working on the population of six million people. What might happen is a nurse calls from the middle of a remote village with a patient with a complex wound on which she is not trained. In the next 24 hours, there is an expert in telemedicine at home with the patient, guiding the nurse via live stream on what to do.” This support continues along the whole healing trajectory. There are also monthly meetings between the experts, providing a forum for continuing education and discussion of complex cases.

So far, the model is allowing the treatment of 300 patients per month and it is on the way to being rolled out nationally. Since it started, NPWT follow up at home increased, especially for complex cases needing NPWTi-d, limiting the cost of ambulance use and hospitalisations. “This is really the future; otherwise, this population is going to continue to be abandoned,” Téot says. In the meantime, his hope is that the new guidance from EWMA will have a significant impact on its own. “My hope is that this document, available for free download, will spread awareness and knowledge about these advanced NPWT methods. We’ve already seen positive reactions and requests for translations in various languages. Making this information widely accessible can help healthcare professionals adopt these techniques more broadly and improve patient outcomes globally,” he concludes.