Diabetes is one of the major scourges of contemporary medicine. In the United States a bewildering one in ten people suffer from the condition, with similar figures emerging from Britain and other Western nations. Yet, if the causes and consequences of these overlapping diseases are generally understood in the medical profession – a lack of insulin for type 1 and obesity and poor diet for type 2 – the same can’t always be said of the wider public. According to research by the World Health Organisation, in fact, half of all sufferers don’t even know they have diabetes. This can quickly encourage serious problems, with diabetes ultimately to blame for hundreds of thousands of deaths related to diseases of the heart and kidneys each year.

But if diabetes is an effective killer on both sides of the Atlantic, it’s equally responsible for a shocking number of amputations. Once again, the statistics from the US are instructive here, with 73,000 diabetic Americans obliged to have a lower limb removed each year.

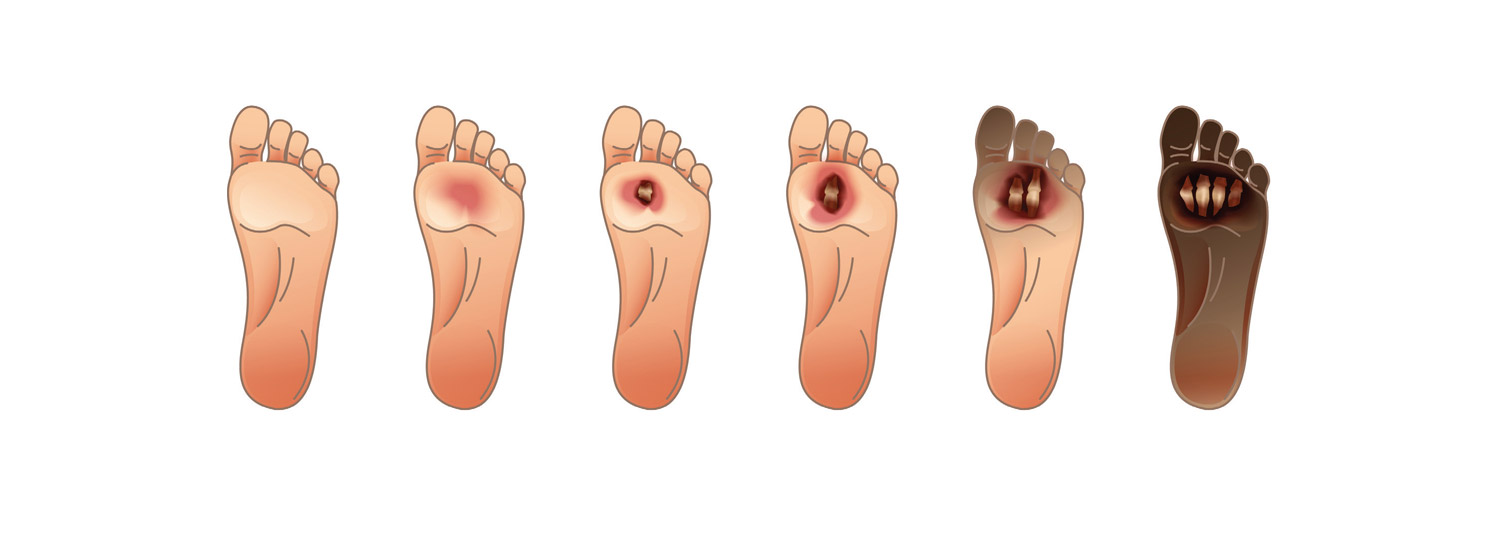

Not, of course, that diabetes causes these amputations directly. Rather, doctors are forced into conducting operations thanks to a condition called diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs) – which themselves stem from the way in which diabetes impacts the body. From poor circulation to foot deformities to a lack of feeling in the foot, there are a range of triggers here. The same can’t be said of the consequences: as Professor José Luis Lázaro- Martínez of Complutense University of Madrid warns, people who undergo major amputations have a survival rate of just 60% over five years.

Not that the medical profession is indifferent to these challenges. For one thing, new technology and better therapies are drastically improving the way in which DFUs are treated, sparing many the physical and psychological trauma of amputation along the way. That’s shadowed, moreover, by the administrative revolution of the so-called ‘fast-track pathway’ (FTP) method. Less a specific cure than a philosophy of care, it brings together doctors and nurses to spot and treat DFUs quickly and effectively, an approach that not only brings obvious benefits to patients – but can also help cash-strapped hospitals keep their coffers full. That is, of course, if staff can work together to integrate the FTP into their working rhythm – not always easy in big medical institutions with the usual mix of competing interests and clashing personalities.

Out for blood

Speak to Dr Marco Meloni and it’s hard not to get depressed at the frequency of foot ulcers in people with diabetes. “DFU’s are very common in patients with diabetes,” stresses Meloni, of the Diabetic Foot Centre at Rome’s University of Tor Vergata. “It has been estimated that approximately 19–34% of diabetic persons have a risk to develop a DFU during their lives.” Appreciate the symptoms of the disease and this epidemic isn’t hard to understand. Most fundamentally, that’s true in the way that elevated blood glucose levels, the hallmark of a diabetic, can stiffen arteries and narrow blood vessels – both facts that stop the body from healing itself, and can promote ulcers to form. The same is true of poor circulation, as well as how the foot deformities common in diabetics can spark pressure ulcers. Even more striking, adds Meloni, is the issue of neuropathy. Damaging the nerves in limbs, diabetes can make sufferers lose their sense of touch – meaning that someone may have developed a DFU without even realising.

“It has been estimated that approximately 19– 34% of diabetic persons have a risk to develop a DFU during their lives.”

Dr Marco Meloni

Whatever the spark, at any rate, the impact of DFUs is impossible to ignore. Putting aside the mortality rates associated with amputations for a moment, that’s obvious from an institutional perspective. For one thing, Lázaro-Martínez explains, the typical hospital stay for someone with a DFU is “approximately double” that for other conditions, a situation that can naturally have knock-on effects in countries like his native Spain, where one Madrid hospital lately had a bed shortage stretching into the dozens. There’s a financial angle here too. From initial antibiotics to long-term rehabilitation, dealing with amputations is expensive, especially if you factor in the lost economic potential of someone limited professionally by an amputation.

Things can be similarly desperate up close as well, with foul smells, calluses and fluid discharge, it’s perhaps no surprise that doctors have traditionally been keen to amputate affected areas, especially as leaving wounds to fester can often lead to sepsis and gangrene.

It’s equally unsurprising, meanwhile, that researchers should have battled so hard for a more satisfying medical solution. Over recent years, there have been a number of advances here, including managing the blood glucose of at-risk individuals, and keeping wounds wrapped and moist. That’s a far cry from older ways of thinking – which wrongly led to ulcers being left uncovered. “Fortunately,” summarises Meloni, “a great improvement in knowledge and tools available for physicians has been achieved.”

Feet first

Yet, speak to both Lázaro-Martínez and Meloni, and it’s clear that the most exciting development in fighting DFUs is the FTP. Lázaro-Martínez speaks for both experts when he describes this approach as “a simple tool” to ensure that everyone up and down a healthcare chain can recognise a DFU – then get vulnerable patients the care they need before surgeons ever need to wield the knife. This can essentially be understood as a question of timing: the faster a DFU is sorted, the less likely amputation becomes. Indeed, Meloni emphasises that many avoidable amputations, even in wealthy countries with robust health services, happen precisely because of delays.

But beyond the broad principle, how does the FTP, jointly developed by the International Diabetic Foot Care Group and D-Foot International, actually work in practice? Probably the simplest explanation is that it’s a flowchart, colour-coded and with straightforward instructions for healthcare professionals to look out for. If, for instance, there are ‘signs of infection’, it means that the patient likely has a ‘complicated’ DFU. In this case, they should receive specialised attention within 72 hours. If, on the other hand, the wound already looks like it’s developing sepsis, the individual concerned should be hospitalised within just 24 hours. From there, the FTP offers a range of options for specific care hints, spanning everything from management in the community to surgery. The point, says Lázaro- Martínez, is that a DFU is referred from “primary care to the hospital” promptly and efficiently.

Fortunately, there are signs that the FTP in all its simplicity can dramatically bolster medical outcomes. According to work by Meloni’s research team in Italy, for example, implementing an FTP led to a significant increase in the number of early referrals of DFU patients. The decline in late referrals – down to just 20.5% of cases from a peak of 60% – was just as dramatic. It goes without saying, Meloni adds, that this kind of shift can have significant consequences for doctors and patients alike. “The FTP,” he says, “may be a very useful tool for a global network between primary care and dedicated hospital to avoid delayed referral and identify severe DFUs early”. That hospitals, and indeed society at large, can also avoid the heavy expense that comes with amputations is a happy bonus too.

A multidisciplinary approach

Of course, a procedure as comprehensive as an FTP can’t simply be implemented at will. On the contrary, liaising closely between primary doctors, DFU consultants, podiatrists and cardiovascular surgeons requires work, with both experts agreeing that a genuinely “multidisciplinary” stance is the key to success. As Meloni vividly puts it: “Diabetic [foot ulcers] is a multi-disease requiring a multi-specialist approach.”

Certainly, this makes sense from a medical perspective. If, after all, a general practitioner isn’t trained to spot signs of sepsis in an infected foot, they’re hardly unlikely to refer a patient fast enough. Once they get to hospital, meanwhile, a nurse will need to diagnose them quickly – to say nothing of the attention patients will need once their crisis abates and they’re discharged home.

Clearly, all this is a medical challenge of the first instance – and not only theoretically. In Italy, to give one example, Meloni explains that dermatologists are “rarely involved” in the fight against DFUs. For that to change obviously requires better training and stronger awareness. But more than that, you get the feeling that the biggest barrier to the wider implementation of FTPs might come in the form of sluggish administration. Lázaro-Martínez illustrates the problem well. “In some places,” he admits, “there isn’t a good relationship between different departments. In others, people have different perspectives of the same disease – and in the end it’s difficult to get people to set up a multidisciplinary team.” All the same, Lázaro-Martínez is convinced that the potential for awkward meetings and tension is worthwhile. Given how brutal DFUs can often be, it’s hard to disagree.